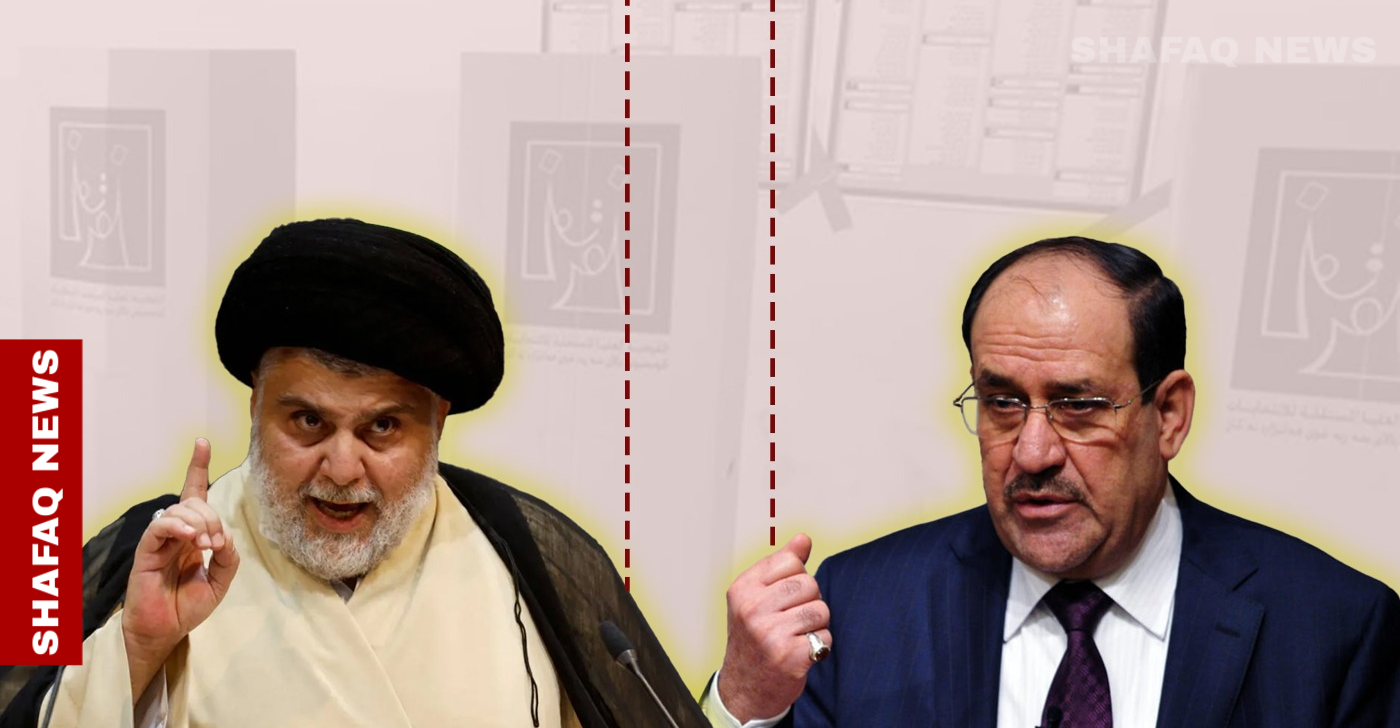

Iraq's political enigma: The unpredictable maneuvers of Muqtada al-Sadr

Shafaq News

For more than fifteen years, the sudden “retirements” and repeated political maneuvers of Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, leader of the Patriotic Shiite Movement (formerly Sadrist), have dominated Iraq’s political scene, each announcement reshaping power within the Shiite camp and influencing the broader national landscape.

From being a reluctant ally of former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki to later demanding his removal, and from leading protests with chants of “Eradicate Them”, a slogan he used to target the political elite he blamed for government mismanagement and corruption, to repeatedly withdrawing and returning, al-Sadr has remained an unpredictable force. He often announces his retirement at the peak of a crisis, only to reemerge and reshape the political game in unexpected ways.

The First Crisis

Al-Sadr’s confrontation with the political establishment dates to 2010, when he opposed al-Maliki’s second term after clashes in 2008 between Iraqi forces and his Mahdi Army (Saraya Al-Salam), an armed faction he later disbanded.

Following months of deadlock after the 2010 election, the Shiite National Alliance, which includes major parties, reached an agreement on October 1, 2010, to back al-Maliki for another term. Al-Sadr’s bloc, with 39 seats, joined al-Maliki’s State of Law coalition, which held 89 seats, a move that proved decisive for al-Maliki’s return to office.

The alliance quickly unraveled. Al-Sadr later aligned with efforts to withdraw confidence from al-Maliki, raising concern in the government and effectively splitting the Shiite bloc. The reversal turned their relationship into a defining rift within Shiite politics.

Storming the Zone

In March 2013, al-Sadr threatened to withdraw from parliament, describing the legislature as “feeble.” By August, he formally announced his retirement from politics. A year later, in February 2014, he reiterated the decision, ordering his movement’s offices closed even though it had won 36 seats in parliament.

What many Iraqis described as frustration over corruption and inadequate services soon brought al-Sadr back to the streets. Protests began on May 31, 2015, in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square and grew into weekly rallies.

When al-Sadr joined in March 2016, chants of “Eradicate Them” spread, and he encouraged sit-ins at the gates of the Green Zone, the fortified district in central Baghdad housing government offices and foreign embassies. Days later, he pitched a tent inside the compound, while his supporters camped outside its walls.

The confrontation escalated on April 30, 2016, when thousands of his supporters stormed the Zone after parliament blocked Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi’s proposed cabinet reshuffle. They withdrew the following day.

Read more: Al-Sadr tightens grip from outside politics, sets high bar for return

Cyclic Retreats

On October 4, 2018, al-Sadr announced another withdrawal from politics, emphasizing that his Sairoon Coalition would not nominate candidates for the new government. In December 2019, he ordered his movement’s institutions shut for a year, including the social media accounts of his close aide Mohammed Saleh al-Iraqi, known as “al-Sadr’s minister.”

On July 15, 2021, al-Sadr announced his seventh withdrawal, stating he would not participate in elections due to corruption. Within three months, he reversed course, allowing his bloc to contest the October 2021 early election, where it secured the largest number of seats.

The election followed mass protests in 2019 that forced Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi to resign. Demonstrations, fueled by anger over corruption, unemployment, and poor services, had swept Baghdad and southern provinces.

It was on June 15, 2022, when al-Sadr left politics again, directing his 73 lawmakers to resign after his bloc failed to form a government. Two months later, he declared what he described as his “final” retirement, closing his offices except for family shrines and heritage institutions. He pledged not to participate in politics again.

In recent weeks, the cleric reaffirmed his boycott of the November 11 parliamentary election. Responding to a letter from President Abdul Latif Rashid urging him to reconsider, Al-Sadr affirmed: “I will not be a partner of the corrupt,” adding that his call to boycott was not aimed at delaying or cancelling the vote but at protesting endemic corruption.

Read more: Iraq's political crossroads: Al-Sadr's boycott,Al-Hakim's mediation

Plot and Paths

Tensions intensified in the last days, after activist Ali Fadhil claimed that there was a plot to assassinate al-Sadr during a visit to his father’s shrine in Najaf, using an armed drone allegedly linked to State of Law MP Yasser Al-Maliki.

The claims prompted deployments by Saraya al-Salam, al-Sadr’s military wing, in several provinces. al-Maliki issued a statement rejecting the allegations, describing them as “fabrications aimed at sowing strife,” further indicating he would pursue legal action.

Al-Sadr responded by urging calm, warning that his movement would not be drawn into disorder. “Such leaks will not cause sedition,” he emphasized, highlighting that his movement relied on “the awareness and patriotism of its supporters.”

Read more: Concerns and boycott: Will the Iraqi November elections proceed on schedule?

A contact close to al-Sadr informed Shafaq News that al-Sadr has increasingly isolated himself, consulting only a narrow circle of confidants. His recent messages, the contact noted, point to a more cautious yet sharper assessment of Iraq’s political crisis.

Al-Sadr is reportedly weighing three potential paths: returning to the streets with protests and sit-ins that could disrupt the election; allowing the vote to proceed while urging a boycott, which could depress turnout and challenge its legitimacy; or holding back until regional developments push toward a postponement.

According to the contact, al-Sadr appears to be counting on implicit international backing to withhold recognition of the results if turnout is too low—particularly with banned armed factions expected to participate. Such a scenario could pave the way for an emergency government, with Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani potentially replaced by a figure such as former premier Mustafa al-Kadhimi.

In parallel, the Coordination Framework, al-Sadr’s main Shiite rival bloc, dispatched an envoy offering him the chance to nominate the next prime minister, in return for staying out of the election. Al-Sadr dismissed the offer, keeping his own options open.

Even in retreat, al-Sadr’s presence hangs over Iraq’s politics—never entirely visible, never absent, yet leaving unresolved questions about how far his influence truly reaches.

Written and edited by Shafaq News staff.

Read more: Leaks and smear politics: Iraq’s elections underthe shadow of distrust