Governance or grab? Iraq's economic relief package tests PM Al-Sudani's motives

Shafaq News

With less than two weeks before Iraq’s parliamentary elections on 11 November 2025, the Iraqi Cabinet ignited a fierce debate by announcing 22 wide-ranging economic and service measures — most prominently the allocation of residential land to educational staff.

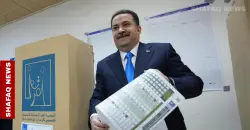

The package, issued at the Cabinet’s 43rd regular session, arrived at a moment when timing and optics are everything. Prime Minister Mohammed Shia Al-Sudani is leading the Reconstruction and Development Alliance (Al-Ima’ar wal Tanmiya) into the vote, personally contesting a Baghdad seat as his coalition fields 446 candidates across 12 provinces and vies for 240 seats — the broadest Shiite-led electoral vehicle since 2003.

The measures have been portrayed in two sharply different lights. For critics, the moves look less like governance than like naked electioneering. For supporters, they address long-standing social demands and reflect the limits and cautiousness of Al-Sudani’s administration.

Read more: Failure or feat? A bold assessment of PM Al-Sudani's tenure

Too Late Now

Independent MP Jawad Al-Yasari questioned the timing, arguing the government delayed too long in taking decisions affecting citizens’ lives, “so we question its intentions as they came at the last moment.”

“What is happening today is clear electioneering, aimed at winning votes and appealing to the public” — words that capture the immediate suspicion of many who view last-minute largesse as a political instrument rather than a remedy to policy failures.

The charge of politicizing state resources was reinforced by Zuhair Al-Jalabi, a senior figure in the State of Law Coalition (Dawlat al-Qanoon) of Nouri al-Maliki, who argued that “even the citizens understand that these delayed decisions are explicit electoral messages.”

Pointing to a pattern he believes has emerged under Al-Sudani, Al-Jalabi asserted that the Prime Minister is using all state capabilities — including staff, security, and resources — to hold conferences and programs with electoral purposes.

“Even appointments, land distributions, and bonuses are being leveraged for electoral gains,” he continued, urging a structural remedy to prohibit any official holding a government or security post from running in this or the next election cycle.

Analysts aligned with the skeptical camp highlighted the scale of election spending and public hardship. Political analyst Abdullah Al-Kanani remarked that public trust in any government official is “now nonexistent,” warning that the package “is simply an electoral tool aimed at influencing public opinion.”

He estimated that more than 4 trillion Iraqi dinars (about $3 billion) are being spent on election campaigns while citizens endure economic strain, asserting that the decisions “were not made to correct governance but to prepare the ground for the elections.”

Moreover, political researcher Hassan Al-Kanani reinforced that argument, describing the measures as “gratifying handouts and election bribes,” and contending that “what is happening is the exploitation of power, presenting routine government duties as personal achievements.”

He further urged the Independent High Electoral Commission (IHEC) to monitor any misuse of office or public funds for campaigning and to hold accountable anyone benefiting from their authority in this regard.

Read more: Money, power, and ballots: Iraq's struggle against electoral fraud

Technocrat’s Slow Fix

Those accusations gain traction against the larger backdrop of Al-Sudani’s years in office. He has not been publicly accused of personal corruption, and his tenure lacks the headline scandals that toppled some predecessors. Yet perceptions remain influential. Al-Sudani’s leadership style — cautious, incremental, and risk-averse — has shielded him from scandal but also left him open to criticism for relying on timing and symbolism.

Defenders counter that interpretation with a consistent appeal to separate motive from method. Ali Al-Bidar, a writer and political analyst, viewed the recently approved measures as efforts to correct certain courses rather than as election ploys.

He highlighted implementation as the real test, noting that the issue “lies not in the decisions themselves, but in their implementation mechanisms.”

“Al-Sudani is cautious in using authority or public funds. He is also aware of high levels of public scrutiny, which prevents unilateral action as in the past,” he observed, stressing that this carefulness is precisely what supporters cite as evidence against claims of opportunism.

Meanwhile, Mohammed Al-Samurrai — an election candidate with Al-Sudani’s Reconstruction and Development Alliance — rejected accusations of electioneering, framing the recently approved measures as routine governance.

“Many of these measures require months to implement, so they cannot be described as election propaganda,” he remarked, emphasizing that they are “essentially service-oriented decisions coinciding with the election period.”

“Announcing a land allotment or a benefit does not instantly translate into finished delivery at the ballot box,” he added.

Across this debate runs a subtle, recurring question about character and habit: is Al-Sudani a leader who quietly uses office to consolidate advantage, or a cautious technocrat who prefers gradual fixes to headline reforms?

The public record and available commentary point in both directions. He has avoided personal corruption scandals, yet his careful posture makes public acts — especially near an election — easy to interpret as strategic.

That ambiguity forms the article’s central tension: the same traits that have shielded him from controversy also make his motives opaque when government action coincides with political opportunity.

Read more: Iraq’s 2025 Parliamentary Elections — What You Need to Know

Written and edited by Shafaq News staff.