Discover Iraq: Karbala, where memory breathes and future beckons

Shafaq News

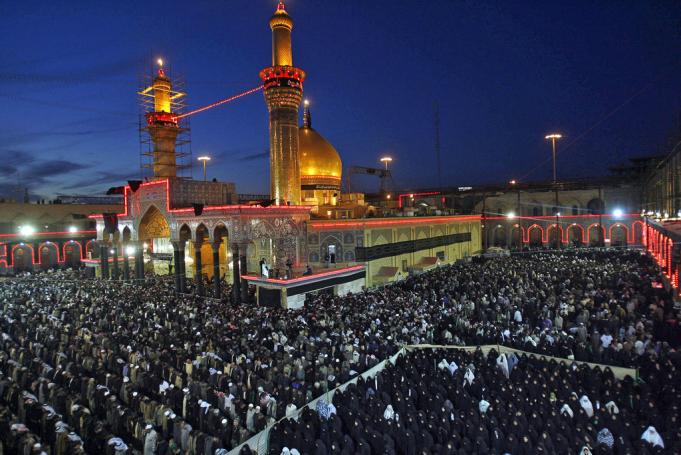

Few places wear their history as openly as Iraq’s Karbala. Each year, during Ashura and Arbaeen, the city fills with black-clad pilgrims mourning the martyrdom of Imam Hussein ibn Ali, the Prophet Muhammad’s grandson, who was killed there in 680 CE while standing against tyranny. His death cemented Karbala’s place at the core of Shiite identity as a lasting symbol of sacrifice.

Yet Karbala’s story didn’t end on that battlefield. Under Abbasid, Safavid, and Ottoman rule, Karbala grew into a center of scholarship, art, and pilgrimage. Foreign travelers noted its wealth, with British explorer Austen Henry Layard once describing Karbala as “one of the richest cities in Mesopotamia.”

Periods of violence did not halt the city’s evolution. After the fall of Saddam Hussein’s government in 2003, Karbala’s shrines reopened to international pilgrims. In the years that followed, terrorist attacks frequently targeted the gatherings, but the number of visitors continued to grow.

In 2024, the Arbaeen pilgrimage drew an astonishing 22.5 million visitors, according to Iraq’s Ministry of Interior, making it the largest annual religious gathering on the planet, surpassing even the Hajj (annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca in Saudi Arabia). As historian Abbas al-Saidi put it, “In Karbala, history is not behind us. It walks with us every day.”

Heartland and Humanity

Karbala, located about 100 kilometers southwest of Baghdad, spans roughly 5,034 square kilometers where desert meets fertile plain. The Euphrates River cuts through the province, offering a narrow lifeline in a landscape dominated by arid conditions. Summers routinely push temperatures above 45°C, while annual rainfall often falls short of 100 millimeters.

The province is home to around 1.4 million people, predominantly Arab Shiite Muslims. A small Turkmen minority remains, and remnants of a once larger Christian community are still visible in stone churches nestled within the older parts of the city. Arabic is the main language, though Persian influences persist in local expressions and traditions.

In Karbala’s rural areas, daily life follows a slower rhythm

shaped by tribal customs and longstanding social structures. In contrast, the

city center moves at a faster pace, fueled by a younger population seeking to

balance religious tradition with new aspirations. “We live between two worlds,”

said Zahra al-Janabi, a university student. “Our faith defines us, but our

future demands we innovate.”

Growth and Grit

In Karbala, pilgrimage is not just a sacred act, it is the heartbeat of an entire economy. According to the Iraq Central Statistical Organization, religious tourism fuels over 62% of Karbala’s GDP. During Ashura and Arbaeen, the city swells with millions of visitors, creating a massive seasonal economy, injecting an estimated $1.5 billion into the local economy.

According to the Karbala Chamber of Commerce, hotels and guesthouses during peak seasons achieve occupancy rates above 95%, while small businesses, from mobile vendors to taxi drivers, see revenues spike by up to 300% compared to regular months.

The scale of hospitality is staggering. In 2024, more than 14,000 Mawkibs (volunteer service tents) were registered with Karbala’s Provincial Government. These tents distributed an estimated 95 million free meals over the 40 days leading to Arbaeen, according to official tallies.

“We don’t serve pilgrims for profit; we serve them for honor,” explained Haj Jassem al-Sultani, a Mawkib organizer whose family has offered free meals on the Najaf-Karbala route for three generations.

Yet this monumental system is also Karbala’s greatest economic vulnerability. The COVID-19 pandemic offered a harsh lesson: When borders closed and pilgrimages were suspended, Karbala’s religious tourism revenues collapsed by 78% in 2020. Thousands of hotels, restaurants, and vendors shut down, and unemployment spiked by an estimated 30% province-wide.

Even today, local economists like Professor Hadeel al-Azawi warn that over-reliance on pilgrimage remains a “single-crop economy risk.”

“If Arbaeen is disrupted, whether by pandemic, political unrest, or regional war, Karbala’s economy could face catastrophic contraction within months,’’ she stresses.

Beyond the spiritual roar of Karbala’s shrines, a quieter but crucial struggle plays out in its fields and factories. Historically, Karbala was famed for its agricultural bounty, particularly in areas like Ayn al-Tamr, revered for its dates, and the al-Hindiya district, known for wheat and barley.

In the 1970s, Karbala produced approximately 250,000 tons of wheat annually. Today, wheat production has shrunk dramatically, dropping from 180,000 tons in 2018 to just 110,000 tons in 2024, a 39% decline driven by water shortages, desertification, and outdated irrigation techniques.

Water scarcity has become existential. According to Iraq’s Ministry of Water Resources, water allocations to Karbala’s farmers fell by 43% between 2019 and 2024, forcing many to abandon traditional crops. In Ayn al-Tamr, once the cradle of Iraq’s finest dates, palm tree numbers have declined by 17% over the past decade due to pests, heat stress, and neglect.

"Palm trees were our pride," lamented agricultural engineer Samir al-Rubayi. "Now, you walk through dying groves where there was once an ocean of green."

Efforts to modernize agriculture are underway. Drip irrigation systems are being introduced under the Smart Farms Karbala project, funded by the Ministry of Agriculture and a United Nations grant. The initiative aims to convert 5,000 hectares to water-saving technologies by 2027.

Meanwhile, the industrial sector provides a critical buffer, if still an underdeveloped one. The Karbala Refinery, operational since 2022, refines 140,000 barrels of oil per day, meeting about 30% of Iraq’s gasoline needs. The project employs over 5,000 people directly, and another 12,000 indirectly in supply chains ranging from transportation to chemical industries.

Smaller factories in cement production (like Karbala Cement Plant) and food processing, especially date syrup and tomato paste, collectively employ about 18,000 workers, according to the Provincial Directorate of Industry.

Nevertheless, challenges abound. A 2024 government audit

revealed that 65% of Karbala’s industrial facilities operate below 50% of their

capacity due to chronic power outages, weak infrastructure, and competition

from cheaper imported goods.

Vibrant Canvas

Karbala remains a global epicenter of poetry and lamentation arts, where traditions of eloquence continue to flourish. Each year during Ashura, the city draws poets from Iraq, Iran, and Lebanon to its renowned competitions. In 2024, Karbala hosted the International Marsiya Festival, gathering more than 400 poets and over 8,000 attendees for readings that wove together centuries-old elegies and contemporary interpretations, affirming the city’s enduring literary spirit.

The creative energy extends into education and youth initiatives. The University of Karbala, now home to more than 27,000 students across 16 colleges, including law, engineering, medicine, and fine arts, has become a vital source of cultural dynamism. Within its Department of Media and Fine Arts, a new wave of projects is taking shape, encouraging short filmmaking, digital storytelling, and visual arts. These programs offer young creatives fresh platforms to articulate their narratives, moving beyond the traditional confines of religious expression.

This growing momentum culminated in 2023, when Karbala launched its first independent film festival, the Karbala Short Film Days. Featuring 22 films crafted by local talents, the festival brought forward stories of women’s empowerment, environmental struggles, and social change. Film director Noor al-Tameemi described the moment as a breakthrough for the city's evolving identity. “For the first time, we showed that Karbala can tell its story in many voices, not only through mourning, but also through dreams, struggles, and hopes,” she reflected.

Religious education, long a cornerstone of Karbala’s identity, is also evolving. The Hawzas (traditional Islamic seminaries) that continue to attract students are beginning to reshape their curricula. Within the Najaf-Karbala theological corridor, new courses in social sciences, economics, and environmental ethics are being introduced, aiming to bridge traditional faith teachings with contemporary challenges faced by modern society.

Intellectual life outside formal institutions is thriving as

well. After a decade-long hiatus, the Karbala Book Fair returned in 2022 and

has quickly reclaimed its place in the city’s cultural calendar. By 2024, the

fair drew over 80 publishing houses and welcomed 45,000 visitors, reflecting a

growing appetite for broader literary engagement. Bookseller Haidar Karim

observed the transformation first-hand, remarking, “There’s a thirst for new

ideas in Karbala. Faith here is strong. But minds are opening too.”

Challenges on the Horizon

Karbala’s path forward is anything but straightforward. Environmental degradation casts an ever-deepening shadow over the province’s future, reshaping landscapes and livelihoods alike. A 2023 report by the Ministry of Water Resources exposed the scale of the crisis: 43% of Karbala’s land now suffers from desertification, fueled by the Euphrates River’s decline and inefficient irrigation methods.

The consequences are no longer confined to dry soil. Dust storms, once rare, have become an unsettling norm. Today, they sweep across the city more than 20 times a year, triple the frequency recorded two decades ago, clouding the skies and choking daily life.

Farmers, already struggling with parched fields, face even graver warnings. According to the Directorate of Agriculture, without urgent reforms, Karbala could lose 30% of its farmland by 2030. In a province where the identity of entire communities is rooted in agriculture, such a loss would ripple far beyond economics.

Meanwhile, economic fragility mirrors the environmental strain. Over 70% of Karbala’s workforce depends directly or indirectly on religious tourism, according to a white paper by the Iraqi Economic Forum. Economist Ali al-Dulaimi urged a dramatic pivot toward sustainable sectors like green energy, education, and high-tech agriculture. “Karbala must prepare for a future where tourism alone is not enough,” he emphasized, highlighting the urgency behind his call.

Large-scale infrastructure projects, once envisioned as lifelines, have also struggled to materialize. The Karbala International Airport, launched in 2017 with grand expectations, remains incomplete. Runways have been laid, but political disagreements and funding shortages have kept the airport dormant. If completed, Provincial Council Member Fadhil al-Issawi explained, it could handle up to 3 million passengers a year, relieving mounting pressure on Baghdad’s overburdened airports.

Yet even against this backdrop of environmental, economic, and political obstacles, new currents of hope are beginning to stir. More than 60% of Karbala’s population is under 30, and a growing number of young residents are charting their own future, untethered from the limitations of the past. Start-ups in renewable energy, environmental protection, and digital innovation are slowly reshaping the economic landscape.

One symbol of this emerging spirit is the Green Belt Project, an ambitious grassroots campaign aiming to plant one million trees in Karbala within five years. It is not merely about greenery; it represents a collective determination to reclaim the future. As activist Ali al-Khafaji put it, “We carry the memory of Karbala in our blood. But we also carry the future in our hands.”

Written and edited by Shafaq News staff.