The Last Bathhouse Keepers: Ancient hammams fight for survival in Iraqi Kurdistan

Shafaq News – Al-Sulaymaniyah

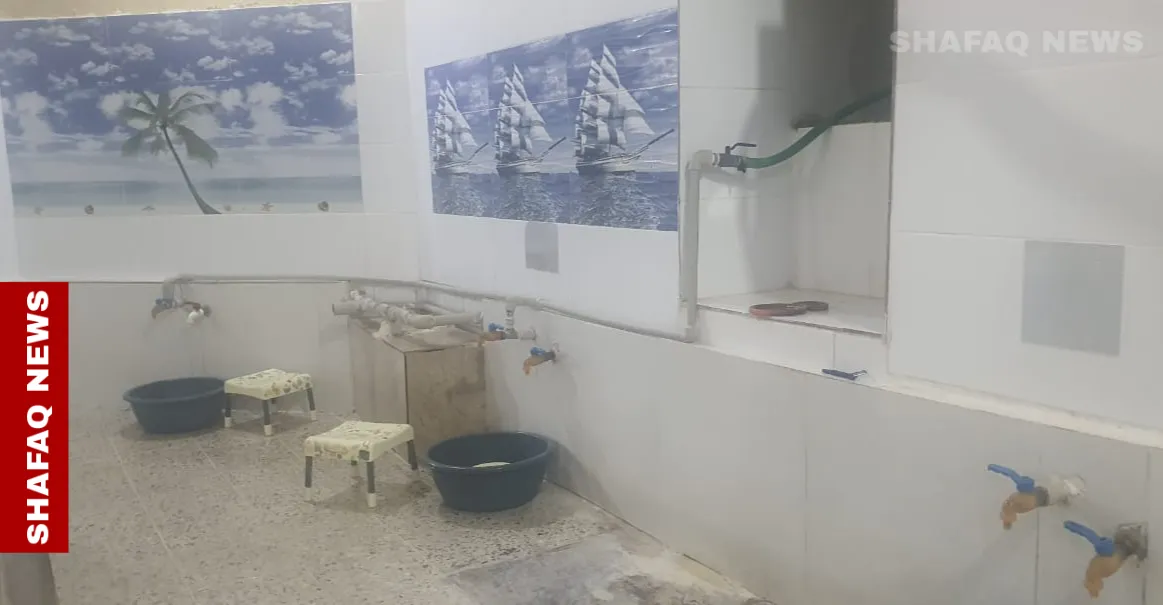

In the old alleyways of Al-Sulaymaniyah, where more than two centuries of heritage endure, Hammam Surt — one of the city’s oldest public bathhouses — struggles to survive as economic pressures and strict preservation rules push this living tradition toward extinction.

Historical records show Hammam Surt dates back to the Baban era. Its name, “Surt” or “Surat,” is believed to come from paintings and images that once decorated its dome before decaying over time.

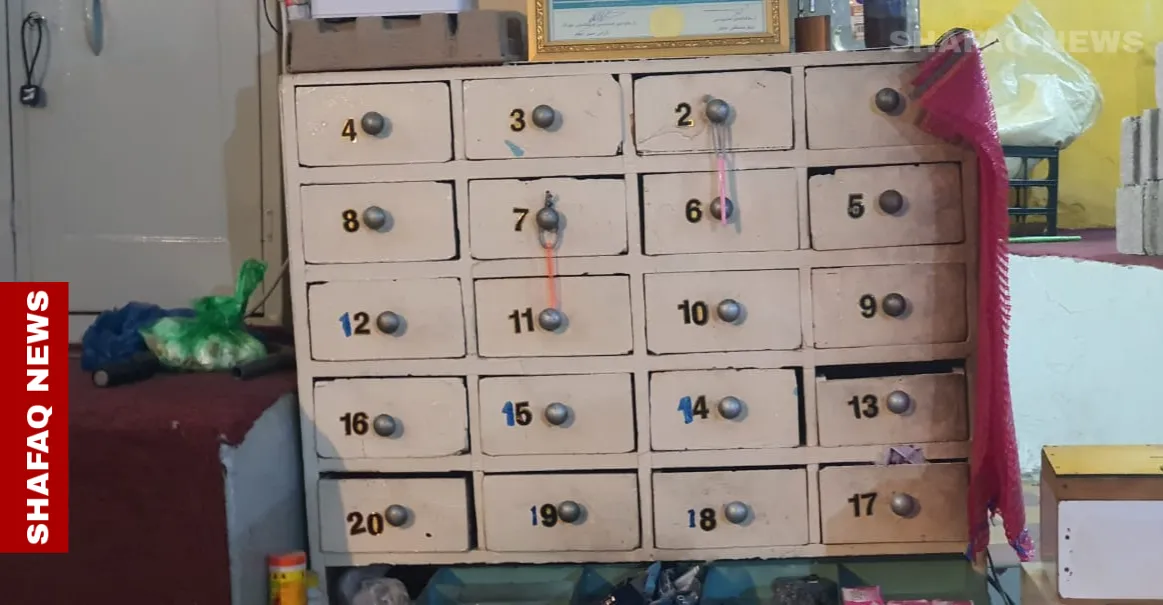

Once a bustling hub of community life, the bathhouse now faces falling attendance and soaring operating costs that threaten to extinguish what remains of Al-Sulaymaniyah’s historic hammams. The city once had 21 bathhouses – only four remain in the center today.

Impossible Economics

Bathhouse owner Sarkawt Mohammed, one of the sector’s longest-serving operators, says patronage has sharply declined in recent years due to the absence of government support and a dramatic rise in fuel prices.

“Gas now costs 700 dinars (around 50 cents) per liter, and we need nearly 150 liters a day just to heat the water,” he says. “It’s an enormous cost that doesn’t match our revenue.”

These expenses have forced many bathhouses to shut down or operate at bare minimum. Mohammed’s family has run Hammam Surt since 1965, though its roots stretch back to the city’s founding.

Additionally, visitor numbers fluctuate heavily with the seasons. Summer traffic is nearly nonexistent, while winter offers a modest uptick.

“In winter, two kinds of customers come: long-time regulars and workers, drivers, and visitors from central and southern Iraq,” Mohammed says. “But it’s still not enough."

When asked why traditional bathhouses haven’t been modernized, Mohammed points to antiquities regulations that prohibit any modification — even basic repainting — without formal approval.

“This makes development slow or almost frozen, even though we urgently need upgrades,” he notes.

More Than Bathing

Social historian Abdulkhaliq Sabir says public bathhouses carried deep social importance.

“They were places of communication and rest, part of the city’s daily rhythm, not merely facilities for bathing,” he told Shafaq News.

Their disappearance, he warns, marks the erosion of a significant part of the city’s social memory.

Museums, Not Living Spaces

Government bodies have restored several archaeological bathhouses, such as the historic Fatima Khan Hammam, revived last year with more than 300 artifacts uncovered during excavation. But Mohammed says these efforts do not help active bathhouses struggling to survive.

“These projects focus on antiquities. What we need is direct support — fuel, supplies, operating assistance.”

Uncertain Future

Rising fuel prices, low attendance, lack of support, and restricted development have placed the remaining bathhouses in jeopardy.

Still, Hammam Surt’s owner insists on holding on. “This isn’t just a profession,” Mohammed says. “It’s my family’s history and the history of Al-Sulaymaniyah. We’ll continue as long as we can.”